It was the spring of 2020 and the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Because we couldn’t record programs in Idaho Public Television’s studios, I had started a show out of my living room called “The 180.” It featured people, nonprofits and businesses that had done “180s,” refocusing their purpose or approach. Some were being forced to change because of the pandemic, but others had done so years ago and could therefore be seen as examples for all of us during that fraught time.

One of my first conversations was with Rebecca Kelada, the founding executive director of Surel’s Place, an artists’ residency program and exhibition space in Garden City, Idaho. I knew that creatives of all kinds were going to be hit hard by the shutdowns, because people could no longer gather to look at their work or see them perform. But artists were also in an excellent position to produce work reflective of the times. So I wanted to know how an art organization was going to tread those waters.

For its part, Surel’s Place had decided to launch a virtual exhibition of art by professionals and non-professionals called “The Panorama Project,” with some of the works being available for purchase.

One of the pieces in particular stood out to me. It was a small, unfinished sculpture called “Our Shared Depression.” Made by Hallie Maxwell, then a graduate student at Boise State University, it portrayed a woman on her side, with grooves and holes carved into her body. The juxtaposition of the delicate curves of the woman’s resting body with the angular shapes chiseled into her was striking.

I contacted Maxwell and asked if she could send me other images of her work, which she did, and I was similarly impressed.

Kelada of Surel’s Place agreed. “We think that Hallie Maxwell is an up-and-coming, emerging powerhouse of an artist,” she told me in our interview.

“This piece is basically how I was feeling at the beginning of the pandemic,” Maxwell explained to viewers in an online event in September 2020. “It felt like everything kind of came to a stop and I wasn’t really sure how to really navigate my own life during this time.”

“It is the inside emotions of the figure manifesting on the outside, with the stress and the sadness making these grooves into the body of the sculpture,” she continued.

“I’m actually very surprised that people have liked this one as much as they did, because I myself didn’t like it when I first made it. So I think it’s really interesting that it truly is our shared depression, that people really share this feeling.”

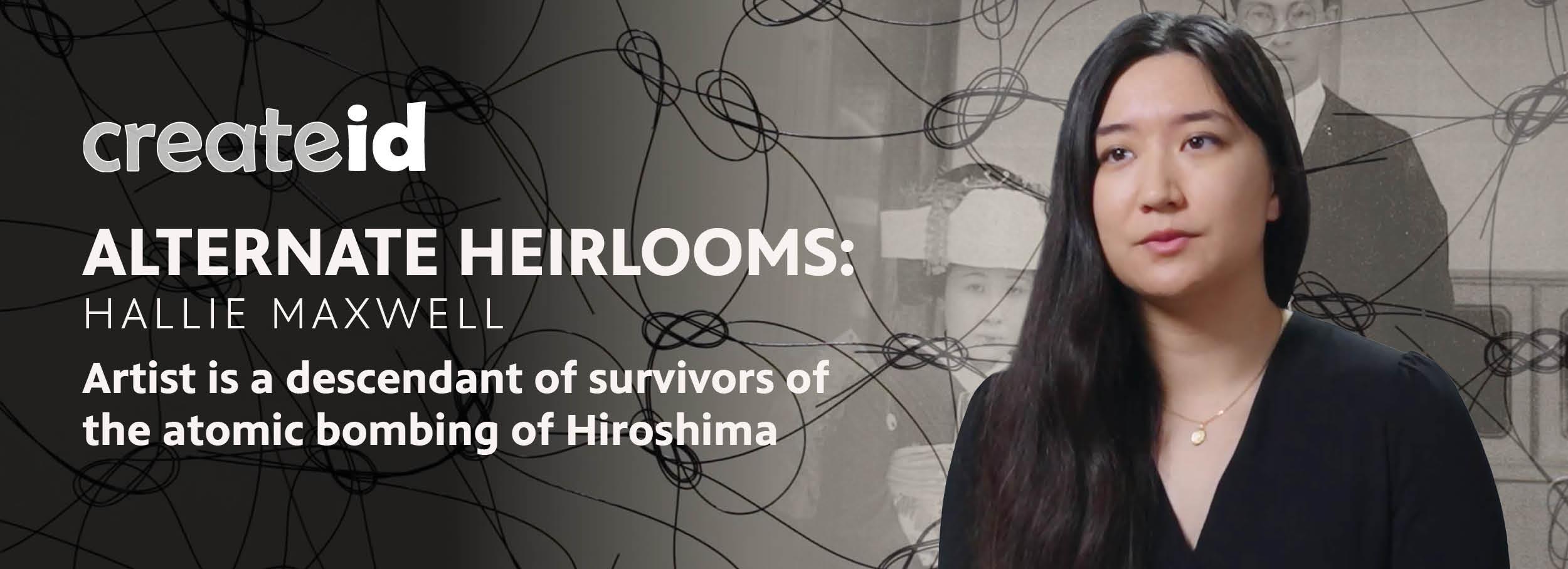

Taken with both her talent and openness, I continued to follow Maxwell’s work, as she was awarded residencies and garnered honors, including the International Sculpture Center’s “Outstanding Student Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award.” She, too, stayed connected with me about her exhibitions. When I learned that she would be exhibiting the works that comprised her MFA thesis, I knew I wanted to do a story about it.

Titled “Alternate Heirlooms,” her thesis examined the ways in which being the descendent of both a victim and survivors of the bombing of Hiroshima still reverberated in her body and psyche generations later. Using multiple mediums, including a traditional Japanese art form of knot-tying, handmade paper and porcelain, a video, and a recording of her grandmother describing the bombing, Maxwell wound together complex themes, including how the stories of our ancestors can be a type of heirloom.

I related to those themes because my own grandparents had to flee their homes in the “old country” due to persecution. I knew they carried a deep sadness about that trauma; even at the end of his life, my grandfather cried about leaving behind his grandfather, whom he never saw again. I could tell that my grandmother was emotionally scarred as well. But I never asked to learn more about what had happened. Now I wish I had, as Maxwell did.

I was fortunate to have parents who were supporters of all forms of art. My father was one of a small group of founders of the Washington Print Club in Washington, D.C., which exists to this day. He also insisted on buying local paintings for his firm’s office, so that their makers would have more visibility. And when the Corcoran Gallery of Art was still in existence (its demise still saddens me) and was sponsoring exhibitions of young artists, my parents would let me pick out a piece of artwork for myself. So from an early age I learned how important it is to support and amplify the work of creative individuals, and how exciting it is to see those artists grow and succeed.

Along those lines, I’m certain that Hallie’s work will continue to be appreciated by even wider audiences, including collectors and museums, and am enthused to see that happen. In the meantime, we’re very pleased that she has joined the createid team to help us with our social media. So you’ll be able to see her talents in another realm as well!